What would it be like to live in a world without guilt? What would it be like to live in a world without forgiveness?

It’s a complex subject, guilt and forgiveness. At times we might feel guilty with no obvious cause. Other times we don’t feel guilty when evidently we should. Sometimes we can get stuck in a kind of guilty orientation to others which leaves us open to exploitation and over responsibility. We’ve probably all tried and felt ourselves fail at forgiving someone who has hurt us. Many of us may have been exposed to a kind of new age zeal which told us to forgive everything and let love cure all.

I understand both guilt and forgiveness have conscious and unconscious aspects. That both can act as defences against other feelings. I might say the right remorseful words that attempt to restore a broken relationship but are a kind of going through the motions in order to appease another person. I might feel guilty myself in order to protect my idealisation of a parent or authority figure who I look up but who has themselves failed me. I might consciously or unconsciously defend my self against my own guilty feelings by going on the attack.

Forgiveness is also a complex business. I can consciously choose to forgive but if this operates as a defence against embracing the hurt I have suffered or the rage I feel in response to that hurt, then all talk of forgiveness is to no avail. Freud’s wonderful paper on mourning and melancholia is useful here. When I have experienced harm from another something has to be mourned, my idealisation of the other, of myself, or of the relationship between us perhaps. In embracing my hurt and rage I surrender any omnipotent thoughts that I should be totally lovable and should live in a world where others behave responsibly and predictably. I embrace life as it is: chaotic, unpredictable, peopled with others in business for themselves, and myself as I am, capable of good and bad behaviour, helpless and helpful, loving and hating.

Psychiatrist Salman Akhtar , for example, sees forgiveness as a marker for certain types of psychopathology and outlines eight syndromes involving forgiveness: “(1) an inability to forgive, (2) premature forgiveness, (3) excessive forgiveness, (4) pseudo forgiveness, (5) a relentless seeking of forgiveness, (6) an inability to accept forgiveness, (7) an inability to seek forgiveness, (8) an imbalance between capacities for self-forgiveness and forgiveness toward others” (p. 189).

Lansky has given perhaps the most detailed attention to the dynamics of forgiveness, linking them to the forgiveness to involve “first the letting go of mental states of ‘unforgiveness’ (resentment, hatred, spite, vengefulness, narcissistic rage, blame, withdrawal, and bearing grudges) and then the gaining of a capacity to tolerate the psychic burdens that attend that letting go: shame, dynamics of shame. In papers focusing on The Tempest and Medea, he considers mourning, loss of omnipotence and of a sense of self-sufficiency, and the task of revising one’s assumption about the nature of relationships”

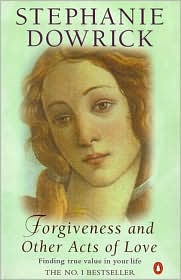

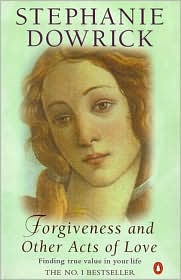

In our local library Stephanie Dowrick’s “Forgivess and Other Acts of Love” is a readable and nuanced exploration of six virtues culminating in a chapter on forgiveness which while encouraging us to free ourselves from resentment and rage, or obsessional clinging to our hurts and therefore to the relationship with the perpetrator also considers that forgiveness is a process which takes time, cannot solely be willed but is also subject to the ministrations of grace. Stephanie Dowrick is a New Zealand born and Psychosynthesis trained therapist and author. Here are some quotes about forgiveness from a more recent book on happiness.

In our local library Stephanie Dowrick’s “Forgivess and Other Acts of Love” is a readable and nuanced exploration of six virtues culminating in a chapter on forgiveness which while encouraging us to free ourselves from resentment and rage, or obsessional clinging to our hurts and therefore to the relationship with the perpetrator also considers that forgiveness is a process which takes time, cannot solely be willed but is also subject to the ministrations of grace. Stephanie Dowrick is a New Zealand born and Psychosynthesis trained therapist and author. Here are some quotes about forgiveness from a more recent book on happiness.

“Forgiveness has it’s own timetable but you can make yourself ready. (‘I will start by focusing on the present instead of going over and over the past.’)”

“Forgiveness happens in small stages. It starts with a determination not to let those past hurts or betrayals dominate your entire existence.”

“Sometimes our greatest rage and resentment is directed towards the people we ourselves have hurt or injured. We may believe that making the ‘wrong’ saves us from feeling bad. It doesn’t.”

“To begin the process of forgiveness you need to let go of the wish that the other person would understand what they have done and suffer for it. They may never understand. They may never suffer enough. That must cease to be your wish.”

My friend Crispin Balfour once suggested to me that our generation was facing a collective guilt, the damage we humans have done to the earth, and that the Green movement could be seen as a reparative gesture in the manner of Melanie Klein for the damage we have done to the nurturing breast of the earth. The question then becomes whether we can embrace this guilt, integrate it and transform it into wise action. Novelist Margaret Atwood in her

massey lectures which have now been published as a book, explores a similar idea in the final lecture she takes a twenty-first

century Scrooge on a journey to meet the Spirits of Earth Day past, present

and future and concludes:

"Maybe we need to calculate the real costs of how we've been living, and of

the natural resources we've been taking out of the biosphere."

"I don't really own anything, Scrooge thinks. Not even my body. everything i

have is only borrowed. I'm not really rich at all, I'm heavily in debt. how do i even begin to pay back what I owe? Where should I start?

After this brief examination of guilt and forgiveness and returning to my

original questions, I feel that although the idea of life without guilt is sperficially appealing, I fear we need to allow ourselves to feel more guilt, not less; and perhaps we need to forgive ourselves for our ignorant waste of the riches of our environmental mother, the earth. In forgiving ourselves, might we then free ourselves to make an appropriate atonement, to repair what we can of the damage done.

Barbara Hammond tells me there are 36 pairs of fairy terns left in New Zealand

and we are about to cut the funding which protects their nesting sites from predation and trampling. Where is our will? It is shown by the kinds of choices we make every day. There's freedom in this as well as responsibility.

Finally let me finish with a Hebrew blessing:

"May everything be permitted you,

May everything be forgiven you,

May everything be allowed you."